Introduction

I mentioned in the preceding post that about a month ago I revisited a nearby chapel, which given the possible presence of ritual protection marks is of interest to this project – more so as a post-medieval foundation (I briefly discuss chronologies with regard to ritual practices in another post). But this site is also of national significance, being one of only three or four churches built during mid-seventeenth-century Commonwealth – and especially so, as built by a noble royalist who died in the Tower of London during its construction, where he was imprisoned on charges of treason. Moreover, this rebel seems to have veered dangerously close to idolatry, by having the vestments of his executed friend, Archbishop William Laud, transformed into an altar cloth and church hangings; and by commissioning murals depicting the Creation (in one of which it is said that Oliver Cromwell is depicted as a dog amid Chaos).[1]

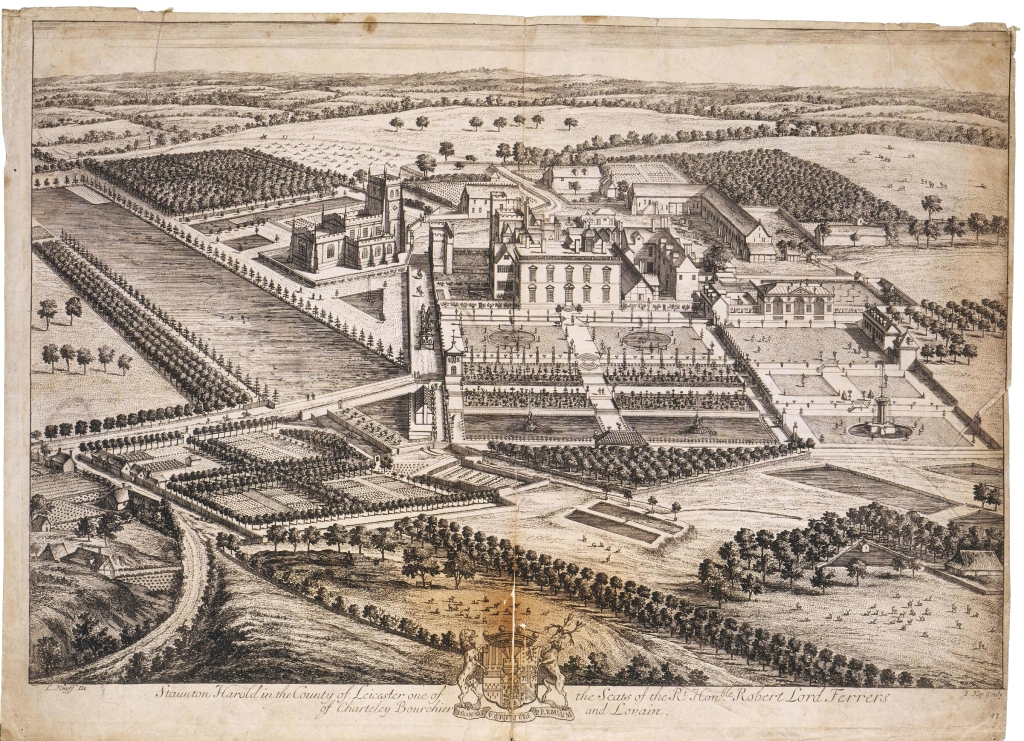

This stimulating site is Holy Trinity Chapel – in the care of the National Trust, but situated within the privately-owned estate of Staunton Harold Hall. The estate is located not far from the South Derbyshire town of Melbourne, and lies just over the border in Leicestershire, close to Ashby de la Zouch (which is why I’ve been able to visit several times).

I’d like to return to the chapel next year to conduct more detailed surveys (and hopefully take more effective photos); and to complete archival research / desk top surveys; with a view to develop this work for publication. But for now, I’ll provide a little more background information on the site; and outline work-in-progress. I’ll also provide information at the end of the post, should anyone wish to visit.

Staunton Harold chapel

Monumental defiance

The chapel was built by Sir Robert Shirley (1629–1656), on his Staunton Harold estate in Leicestershire, beside his family residence. Sir Robert (who had become the 4th Baronet in 1642) began construction in 1653, although work continued posthumously according to instructions left in his will; building was finally completed in 1662-5.[3] The surviving hall (see more information here regarding the park) dates largely to the mid eighteenth century, though incorporates some features of the Jacobean house in which Sir Robert would have lived, and modifications dating to c 1700. (The title of Baron Ferrers was granted to their heir in 1677, and that of Earl Ferrers in 1711 – the 4th Earl, Laurence Shirley, 1720 – 60, perhaps the most famous of the family, being the last peer in England to hang, after conviction for the murder of his steward.)

The estate lies close to the market town of Ashby de la Zouch – a Royalist stronghold during the Civil War; and others in the area defended the Royalist cause (such as the neighbouring Harpur family, at Calke Abbey (another National Trust property well worth a visit), and Hastings at nearby Castle Donington (the existing Donington Hall not built until c. 1790). This bastion of Royalist support met with strong Parliamentary opposition.

Holy Trinity was built on a private estate (the parish church being located at Breedon, where there was a family pew, and burials), and the Baronet had avowed that “he would not suffer any that acted for Parliament to live on his lands”. Yet an Order of Council indicates that Parliament was aware that Sir Robert was building a church on his lands – perhaps due to a warrant issued by the Council of State in 1654 “to seize, inventory and secure all his estates” (although it appears that the former and latter command were not fulfilled.[4]

The chapel is seen as provocatively ‘High Church‘, and a deliberate contestation of the Puritan values that prevailed at this time. An inscription above the west entrance reads:

In the year 1653 when all things Sacred were throughout ye nation, Either demolisht or profaned, Sir Robert Shirley, Baronet, Founded this church; Whose singular praise it is, to have done the best things in ye worst times, and hoped them in the most callamitous. The righteous shall be had in everlasting remembrance.

The chapel might thus represent an unusual, lasting, material trace of beliefs, emotions, and sensations engendered by these tumultuous times – a testament to a faith clearly entangled with a political standpoint that ran contrary to the dominant view: a common, if dangerous, situation in his day. However, the extent to which its construction, as an intentional act of defiance against an intertwined state and church, played a part in the Baronet’s demise is debatable.

While, arguably, construction of the chapel may not have helped Sir Robert’s case during his final incarceration in the Tower of London, he had already been arrested several times before 1653 as a known staunch royalist and suspected rebel, believed to be involved in conspiracies against Parliament. He died in the Tower in 1656, at only 27 years of age, reputedly by poison.[5] If this was indeed the case, it might be speculated that if not self-administered, the fatal dose was inflicted more out of affection than by malice, in order to spare the Baronet the fate of an agonising traitor’s death, or excruciating execution as a heretic).

Decor, Decorative Objects & Deviation

The building & fittings

The interior (more on which can be found here) is little-altered since construction, retaining numerous original and early features – oak box-pews and wall-panelling, pulpit, lectern, and font-cover;[6] some of the original (plain) glass windows; the late seventeenth-century wrought iron chancel screen by Robert Bakewell (the original carved screen relocated to beneath the organ loft); the organ (dated to 1640, and so pre-dating the church); and various significant ecclesiastical artefacts. Thus, numerous elements of the early sensory and material environments of the building remain largely in situ.

What stood out on this visit, more than previously (having since conducted further research into sensoriality), is that to modern eyes, influenced by recent representations in popular culture of royalists at this time as be-laced, feathered and flouncy-fashioned hedonists, the interior might not seem as elaborate as might be expected of an enemy of the Puritan Parliament. The much later stained glass now filling several of the windows stands out against the white-washed walls (which until relatively recently were of bare stone), and the oak panelling and pews – the carvings on which, while ornate, appear relatively restrained when compared to contemporaneous examples within other contexts (though are still ornamented with fashionable devices).

However, to varying degrees such comparisons say more about modern-day perceptions and beliefs that those in the past. What today may be perceived as subtle variations, were likely at the time more evident and obvious (yet largely unconscious) choices that determined contextually-appropriate motifs, materials and finishes. The apparent relative simplicity suggests discerning aesthetic judgements, exhibiting an appreciation of cultural nuances that demonstrate knowledge and education – and consequently, social position and authority.

The numerous hatchments, funerary and heraldic tabards, banners, and helms; gauntlets, helmets, spurs, sword and shields; and other accoutrements; and the few tablet memorials – insignia and monuments found in most parish and estate churches across the country (and both of interest for my research on local and regional post-medieval death & burial)[7] – provide further tangible reminders of the interdependence between the established church, local gentry and nobility, and the local community.

Nonetheless, to mid-seventeenth century puritan parliamentary representatives (and other zealous godly observers), the Devil was (quite literally) in the detail and – however rebellious the spirit – absolutely contravening directives resulting in demolition would likely have done little for the Royalist or (for Shirley, the even more important) Anglican cause. Some degree of restraint (at least with regard to the immovable & inconcealable chapel fabric) may well have been considered judicious. Possible adherence to Parliamentary Ordnance during construction is suggested by the probable delay in fitting the organ (which bears a date of 1686), the installation of organs within churches forbidden during the Civil Wars and Commonwealth period.[8]

Yet the nave ceiling painting (dated to 1655, those in the aisle and chancel perhaps painted several years later, during the Restoration) depicts the Creation – was perhaps controversial at this time. While not incorporating iconic representation, and although the fervour of iconoclasm seems to have dampened by the 1650s, the destruction of devotional images remained a threat.[9] Close inspection of the wall, frame and boards, might say more about the possible ease of temporarily covering, removing , or reversing the ceiling boards, given sufficient notification of ensuing danger. That one board of the southern aisle mural has been turned 180 degrees when replaced after temporary removal perhaps indicates this possibility.[10]

What comes across most strongly when considering the building – which may to varying extents explain many of the stylistic choices made in the construction of this chapel, and the religious practices enacted within – is the general conservatism shown in its construction. In fabric and form, the building evokes a sense of tradition: continuity of what (it may have then seemed to most) had always been – what was natural, and so needful for stability (and at the same time validating the position of local elites such as the Shirleys).

From a distance, the chapel blends into the landscape as an apparent Medieval foundation – the very late Gothic style / very early Gothic revival evoking a sense of security at a time of upheaval. The buttresses, pinnacles and crenellated parapets provided a familiar silhouette in the skyline, a closer view revealing windows with tracery and pointed-arches of the windows: features well known to all. The building was a monument to the all-but eroded former times of ostensible stability – the durable stone a beacon of permanence, when for many the direction of their future lives was surely unclear.[11]

Portable ‘papist’ paraphernalia?

The design of liturgical vessels echoes the Gothic style of the chapel. However, in evoking pre-Reformation ritual practices more directly than the building, their use perhaps heightened the risk of censure from puritan authorities (though their portability – and consequent capacity for removal and concealment with comparative ease – was perhaps to some extent seen to mitigate this risk).

The ‘altar-cloth’[12] and pew hangings (the runners possibly also belong to this collection, along with other items not on display), are of especial interest, and place the Baronet, other worshippers, and the priest at the centre of national politics and religious controversies. Reputedly made from the vestments of the Archbishop Laud – executed for ‘papist‘ practises in 1645,[13] and consequently considered an Anglican martyr – their placement may have effectively rendered these artefacts as post-Reformation relics, potentially exhibiting sympathy with earlier (perhaps even pre-Reformation) practices and material environments.

These hangings are dated to 1665 (after the death of the 4th Baronet), denoting completion of their transformation from vestments to ecclesiastical hangings, and embroidery, by the Little Gidding religious community. Their installation therefore suggests continuity of High Church aesthetics and ideals after the Restoration (when such behaviour and beliefs were again in favour).

Staunton Harold Graffiti

Personal & Religious Graffiti: Gender, Status & Belief

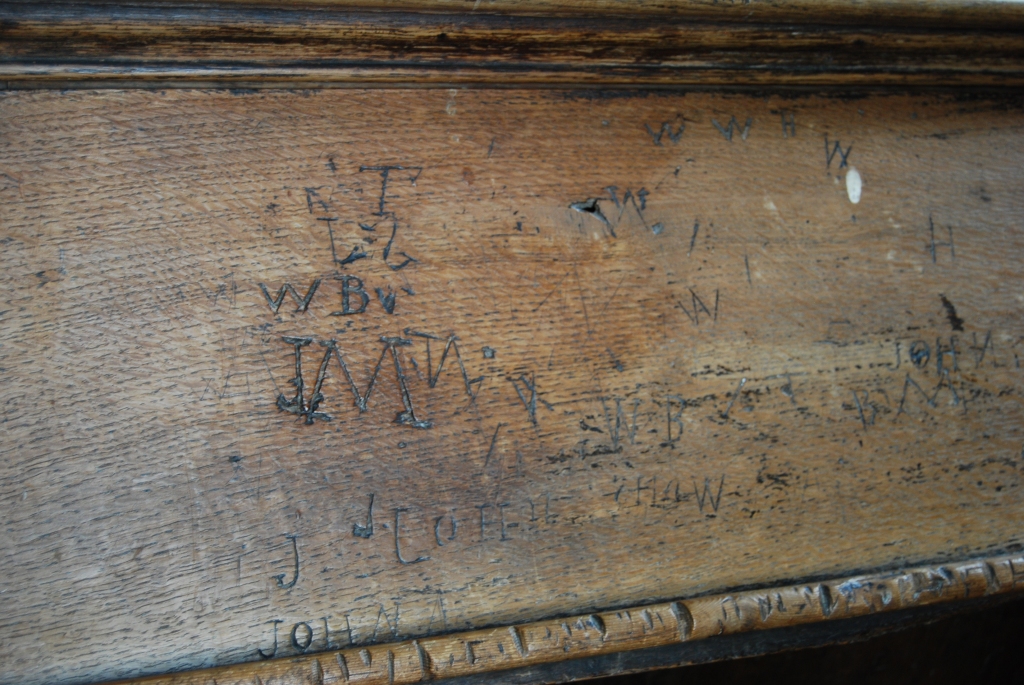

Many examples of graffiti, from various categories found during the Medieval, Early Modern, Industrial and recent periods, are evident within the chapel. The type most familiar to modern observers – personal ‘memorial’ inscriptions and ‘doodles’ – is present in quantities on the box-pews.[14] The distribution of these marks is interesting, being largely confined to the rear pews of the southern aisle. This location at the back, where surveillance of the culprits’ behaviour would have been difficult, is unsurprising. However, as the congregation was (and still is during regular Sunday services) ordered according to rank and gender (and possibly age), this distribution might tell us something about attitudes – manifest through covert behaviour – surrounding social relationships and identities, in the past.

Those with the greatest authority within the church community (inevitably, in this case at least, inseparable from the secular community) tended to occupy the ‘prime seats’ towards the front of the nave, close to the pulpit and altar. This proximity was also often reflected in the location of burial vaults and crypts.[15] To be interred close to the altar not only conveyed social primacy, but to some also brought with it a hope that the ‘spiritual potency’ of the Eucharist – and especially, that of any saintly relics kept by the church – might effectively infuse nearby burials, affecting the passage to and position within Heaven. It was common practice communities for those with sufficient money and power to pay annual fees (often of a guinea – a significant part the yearly income for many of the labouring population) to secure their own pew for family use within their parish church,[16] though estate chapels such as that at Staunton are likely to have been under the closer control of the resident gentry and nobility.

Conversely, pews at the back of the nave, from which view of the pulpit was to varying degrees obstructed by pillars, and the altar out of sight, are likely to have been occupied by those who carried less weight, socially, with limited direct contact with either the incumbent sacred or secular elite on a day-to-day basis. Bonds of duty and obedience may have therefore been less strongly felt, and misbehaviour (in the form of graffiti) perhaps a greater temptation. It might also be argued that this graffiti (some of which is quite elaborate, and would have taken some time to complete) indicates lack of attention to the church service attended by the culprits (possibly even tenuous religious beliefs).

However, an alternative (though perhaps related) explanation for this distribution might be suggested, which reflects a gendered- (rather than class-) basis of such behaviour (in this context at least), perhaps influenced by gendered access to particular categories of material culture. As today, male worshippers occupy the pews of the south aisle, and females, those of the north (where there is little or no graffiti on any of the pews).

This may suggest either greater surveillance (as was – and to some extent still is – in general the case for girls and women, than boys and men – though the enclosure, and height of the pews, are likely to have limit the possibility of observation and supervision); more limited access to the tools – such as pocket-knives – capable of producing such graffiti;[17] or / and different ‘ways-of-doing’ for male and female within the same cultural and social situations. (We might even succumb to stereotypes that have endured for centuries, and suggest that the girls and women were more interested in each other and the rest of the congregation, than in self-expression and ‘making their mark’. However, diaries and autobiographies reveal that imprecision of such generalisations.) Without further evidence we cannot of course be sure whether the girls and women might have been as bored and / or as non-believing as the boys and men might have been, but the adoption of different behaviours (evinced by the absence of graffiti) indicates that gender affected the experience of church attendance in the past. As at other churches, personal graffiti is evident on exterior walls, in locations where gathered groups of people might conceal such activities.

A cross deeply carved into the font represents another category of graffiti found within Holy Trinity, which probably relates to orthodox Christian beliefs and ritual practices associated with the use of this feature in baptism. More research might pay-off with regard to the particular significance of this motif, in this form, within this specific context. Cursory investigations suggest that the style is a variation on the heraldic ‘croix pommée’, which seems to have been first employed during the early seventeenth century.

Mason’s Marks

Numerous mason’s marks, of various forms, can also be seen throughout the accessible sectors of the chapel, and (in a narrower range of forms) on the exterior walls. Regarding their chronology, we cannot assume that all or any of these marks were made during or soon after the time of construction, and should consider the possibility that they may have been made at a later date. However, the date of construction provides a pretty strong terminus post quem of 1653-5: taking into consideration the process and function of mason’s marks, we can be reasonably sure (from the condition of the masonry) that none of the materials on which possible these marks are found had derived from previous structures.

I’m pretty certain that all of these marks relate entirely to construction methods; but given the context of some (their placement; the date of construction, and the social, political, cultural, and religious context touched upon above; and of a form that in some circumstances might be interpreted as apotropaic),[18] these marks perhaps warrant further investigation.

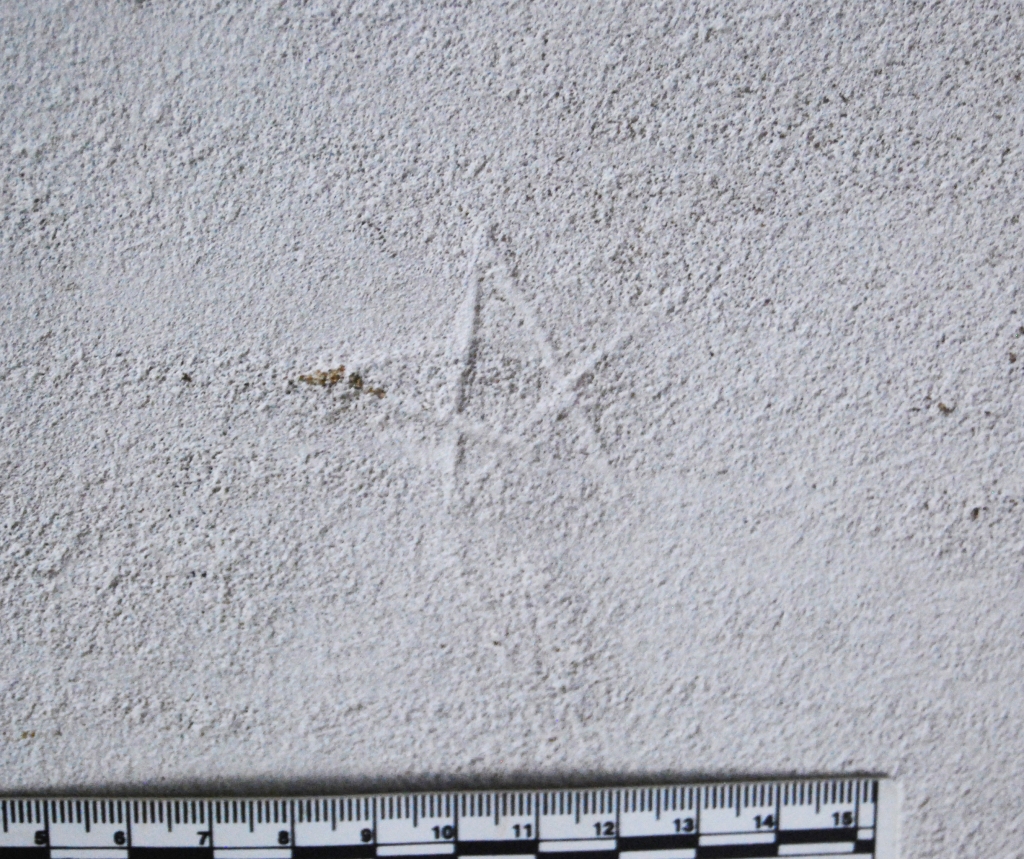

Pentangles

Pentangles are one of the restricted range of motifs associated with apotropaic and other magical practices of the early modern and industrial eras. As mentioned in the another post, this symbol was not generally attributed a demonic significance, or associated with witchcraft, as it is today (in the past a close relationship between witchcraft and the Devil typically imagined to exist). But, as with the six-pointed star, the pentangle was sometimes integrated within alchemy, charms, and divination – forms of magic usually employed by learned (or at least literate) practitioners when appearing within texts. Such practices were not necessarily seen as incompatible with Christian beliefs and identity – indeed, educated ‘magicians’ generally saw themselves as devout Christians (or at least presented such a persona), and these symbols were often used in magic alongside Christian practices (particularly prayer). Understandably, more puritanical observers saw such behaviour as heretical, and abhorrent.[19]

The number of pentangles at Staunton (of which there are many – inside and out); and their presence within ‘liminal’ locations (on window sills and surrounds, and around the west entrance) might suggest an apotropaic significant. However, this symbol was regularly used as a mason’s mark, and its presence would not normally be taken to indicate occult significance without additional, suggestive, contextual information. While most of the marks in the western doorway appear to be pentangles when viewed from below, they are not the only form of incised symbol; and they also often appear among other forms of mason’s marks in a range of locations within (and outside) the chapel. It is of course possible, even probable, that some in the past alternatively, or consecutively, attributed an apotropaic significance to ostensibly profane markings, and vice versa, and possible multivalent properties should not be ignored; but such significance is difficult to prove.[20]

Consequently, it seems more likely that these are simply mason’s marks made as part of the construction process, the plethora of pentangles indicating the presence of particularly prolific mason (or masons). While there’s little chance of finding evidence of sufficient detail that associates the mason’s marks with named individuals, but a trip to the archive might still be of benefit, should there be any further information on constructing of the building.[21] Previous studies of the chapel have brought some evidence to light: on the rear of the chancel parapet is the inscription “Richard Sherpheard Artifex”, giving the name of one signifies is craftsman, and the activities of indicating completion (of at least this architectural element / mason’s work) in 1662/5.[22] Further detailed surveys will perhaps reveal additional information of this form.

‘Marian’ marks

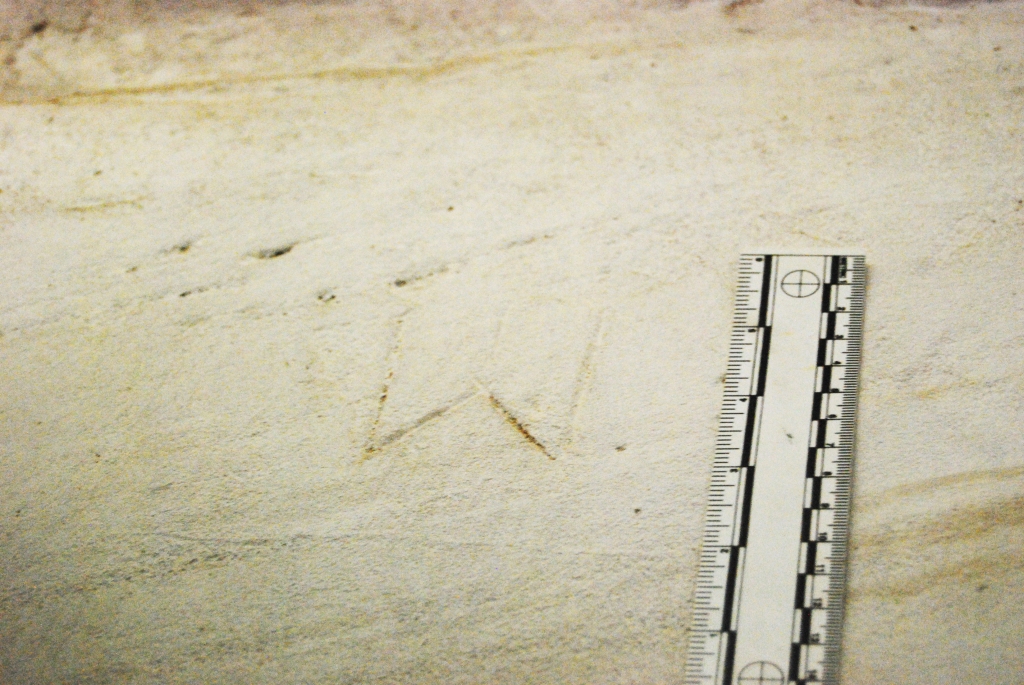

Another symbol commonly attributed ritual significance is the ‘Marian’ mark – usually in the form of ‘M’, or inverted as ‘W’ (often during the seventeenth – early eighteenth century written as crossed ‘VV’s). A single ‘VV’, and an inverted ‘M’ are evident within the door surround of the west entrance. There is also at least one VV mark on the exterior wall.

Again, these may simply be mason’s marks (although it is not one of those commonly found throughout the building): a possible example may be seen high on an external wall, perhaps supporting this argument; or they may represent personal graffiti, although the forms here are not well represented in other media within the chapel (such as the pews). However, as this symbol is, one of the most frequently found within apotropaic contexts (especially within domestic buildings, often around the chimney and hearth), and its location within the doorway here may be important. On the other hand, another ‘M’ is incised into the wall behind the pulpit – in some ways a more ambiguous location. Again, further detailed surveys might reveal additional examples of this form, which like other symbols may well have attracted multiple meanings.

Circular marks

Quite prolific forms of symbols given apotropaic significance are the circle and arc, often found in combination, particularly when arranged to form hexafoils. Several arcs and circles are incised into a door within the porch (which I would anticipate is most usually assumed to be a carpenter’s mark). The door is within the tower (adjacent the main, western, entrance to the church) and leads to the roof (& is thus a particularly ‘dangerous’ area with regard to penetration of the building by any ‘evil spirits’ in the mood to make mischief), which makes these marks good candidates for apotropaia. While the door is probably original (as suggested by the fabric, saw- and adze-marks; and as the later door-furniture appears to be secondary), I’d like to make a closer inspection (for which I didn’t have time on this visit), to be more certain.

Preliminary conclusions

As apotropaic marks within churches are more usually associated with medieval buildings, with post-medieval markings more commonly recorded within domestic and agricultural buildings,[23] the prospect of such marks not only within a post-medieval church, but also at a time when belief and ritual was in turmoil, is of particular interest with regard to the importance of the past (and familiar, stable, practices) in attempting to find stability and hope, especially in the (re)construction of social relations and identities.[24] A complete survey, recording all the marks, their forms, and locations, might tell us much (although this is beyond my scope at present).

At this stage, I feel that there’s insufficient evidence to attribute a primary function of ritual protection for any of the pentangles: the general patterning amongst the multitude of mason’s marks (most of which appear to have been incised by craftsmen as part of the construction process), in general argues against a ritual interpretation. A possible dual-purpose in which the symbol was perceived as both ‘signature’ & protective, is perhaps plausible in the case of those around the west entrance and in other liminal zones, but should for the time being at least be considered as unproved. I need to go back to look more closely at prospective ‘Marian’ marks before I can say much more about this category – a closer consideration of any exterior marks, and of the extent to which this mark is found amongst the more definite mason’s marks, in comparison to individually, may be useful. The compass marks seem more compatible with an apotropaic interpretation, and as with regards other prospective forms, a more detailed survey, in this case of the timber features within the chapel, might be beneficial.

I shall leave further discussion of this site until I’ve completed more research and fieldwork; but if any reader happens to encounter any potentially significant information on visiting the site (or relevant archives) in the meantime, I’d be grateful if they could let me know.

Irrespective of the fabulous history of the site (which may be entered without charge or NT membership), and its own aesthetic pleasures, the park is delightful, and worth a visit if looking for somewhere for a short picturesque stroll or picnic. For those who care for such things, the adjacent Ferrers Centre offers places to eat, drink and shop. But note that there’s a charge for parking (whether or not a member of the NT), and the car park is a few minutes’ walk away from the Centre and chapel (there are a couple of disabled parking places at the centre, but these are likely to be occupied at weekends and holidays).

I must end by thanking the NT for enabling entry to this fabulous site! And give especial thanks to the National Trust stewards who informed and enhanced my visit with their knowledge, and real helpfulness.

Notes

[1] Thanks to a National Trust steward at the site for informing me of the links with Laud and origin of the altar cloth. This steward also relayed the suggestion that the mural portrays Cromwell as a dog; I’m unsure where this hypothesis originated, but intend to look into to it further when returning to study the site.

[2] All photos by the author, unless otherwise indicated.

[3] John Fox (2001), Staunton Harold, which provides a more detailed discussion of the chapel, the estate, Sir Robert Shirley; the role of the family in the Civil War; and their religious affiliations.

[4] Fox (2001), see above.

[5] See Andrew C. Lacy (1982-3), ‘Sir Robert Shirley and the English

Revolution in Leicestershire’, Transactions Leicestershire Archaeological and

Historical Society, Vol. LVII I, pp. 25 – 35

regarding the possible significance of the chapel’s construction in Shirley’s

imprisonment. However, for a note of caution regarding the notion of religious

tolerance during the Civil War and Commonwealth era, see Keith Lindley (2019)

‘Review of Persecution and Toleration in

Protestant England 1558-1689‘, Reviews in History 192,

https://reviews.history.ac.uk/review/192 (accessed 17 -09 -19).

[6] I hope to return to the significance of font-covers with regard to folk magic in another post.

[7] I’m in the process of developing a sister site to discuss this work. In the meantime, many of the photos I’ve taken over the last few years can be viewed online via Flickr, here.

[8] Fox (2001), see note 3.

[9] Fox (2001), see above; while iconoclasm was apparently less active by the 1650s, parliament continued to support spoliation when deemed necessary: see Julie Spraggon (2003), Puritan Iconoclasm during the English Civil War, Studies in Modern British Religious History, Vol. 6, http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.7722/j.ctt81zjt (Retrieved 20 – 09 -19).

[10] With thanks to the National Trust steward for pointing out this board.

[11] See Keith Thomas’ classic work (1971), Religion and the Decline of Magic, for discussion of the significance of the past for mid-seventeenth century political movements and groups such as the Levellers.

[12] In post-Reformation endeavours to expunge ‘popish’ practices, the term ‘altar’ was replaced by that of ‘communion-table’ (on such undertakings, see e.g. Peter Marshall (2017) Heretics and Believers: A History of the English Reformation). This new form of reference is evident locally in various instances: e.g. in 1598 and 1630 at Repton, Derbyshire (albeit by a puritan clergyman): J. Charles Cox (1879) ‘The Registers, and Churchwardens’ and Constables’ Accounts of the Parish of Repton’, Derbyshire Archaeological and Natural History Society Journal, Vol. I, pp. 27-41; in 1613, 1663, 1664, 1669, 1686 & 1687, at St Werburgh’s, Derby: Thomas L. Tudor (1917) ‘Notes on an old Churchwardens’ Account Book (1598 = 1718) concerning the Church and Parish at St Werburgh in Derby. Part I’, Derbyshire Archaeological and Natural History Society Journal, Vol. 39, pp. 192-223.

[13] Again, thanks to the National Trust steward for bringing the origins of this object to my attention.

[14] For a discussion of incised and other forms of Christian cross marks within medieval and later churches, see Matthew Champion (2015), ‘Magic on the Walls: Ritual Protection Marks in the Medieval Church’, in Ronald Hutton (ed.), Physical Evidence for Ritual Acts, Sorcery and Witchcraft in Christian Britain.

[15] However, changes in the law during the mid-nineteenth century (and frequently in the regulations of individual churches during the previous decades) restricted intra-mural (literally, ‘within the walls’) burial, with a general prohibition of urban church- and churchyard-burials.

[16] See, for example, the seventeenth-century churchwardens’ accounts for St Werburgh’s parish, Derby, which lists more than 60 names under “A Remembrance of ane anscientt custom for the Inhabitantts of the parysh of St Warburge to pay for their churche seates”; and that ‘by a resolution at a parish meeting’ in 1686, it was “Ordered that Mr. John Gisborne junr. shall, for the use of himself and family, have and enjoy a certaine seate or pew adjoining or being part of the Parson’s Pew, paying yearly to the churchwardens….the sum of twentie shillings from Easter last past, and immediately after such time as he shall procure an order or license from the Bishop settling himself and family in the said seate, that he shall pay to the then churchwardens of the parrish the sume of twenty Pounds, and from thenceforth the said rent to cease. The said. seate to be set forth by the parson and churchwardens.” Thomas L. Tudor (1918) ‘Notes on an old Churchwardens’ Account Book (1598 = 1718) concerning the Church and Parish at St Werburgh in Derby. Part II’, Derbyshire Archaeological and Natural History Society Journal, Vol. 40, pp. 214-37.

[17] The provision of pocket knives, even small children, is evident from an account book of 1650s relating expenses at Hardwick Hall, Derbyshire: see Rev. F. Broadhurst (1905) ‘Extracts from Book of Accounts of Lady’s Waiting Woman for Moneys dispersed in Cloathes, &c., for Elizth Countess of Devonshire and ffamily. Beginning 1656. Ending 1662.’, Derbyshire Archaeological and Natural History Society Journal, Vol. XXVII, pp. 1-10. However, this case may be exceptional, being that of a son of an earl.

[18] As outlined in a previous post, a large and expanding body of work, within a variety of academic disciplines, recognises the ritual significance of particular patterns of behaviour identified through material remains, and the widespread use of particular symbols in folk-magic and superstitious practices during the early modern and early industrial eras. By examining a range of sources in conjunction, correlation between material remains, written sources, images, and other sources, is evident. I intend to provide a broader discussion of archaeology and ritual in another post.

[19] For example, see Alexander Cummins (2015) ‘Textual Evidence for the Material History of Amulets in Seventeenth-Century England’, in Hutton (ed.), see note 14; Owen Davies (2009) Grimoires: A History of Magic Books; Physical Evidence.

[20] Regarding artisans’ personal (in distinction to professional) graffiti, and the possible overlap of mason’s marks and apotropaic markings, see Timothy Easton (2013) ‘Plumbing a spiritual world’, SPAB Winter 2013.

[21] If anyone knows of or comes across relevant information, and wouldn’t mind be sharing this (of course with recognition of attribution) please let me know.

[22] Fox (2001), see note 3.

[23] Stephen Gordon (2015, ‘Domestic magic and the walking dead in medieval England: A diachronic approach’, in The Materiality of Magic. An artefactual investigation into ritual practices and popular beliefs, ed. Ceri Houlbrook & Natalie Armitage) makes the interesting point regarding medieval domestic carvings and incisions. His suggestion that, while 16th and 17th century households and communities may have been most fearful of witchcraft, earlier activities may represent greater concerns over the walking dead. There are complex reasons why this may have been so, and it is a question to which I hope to return.

I have more generally considered the changing significance in and meaning of ritual acts in K. Jarrett (2013), ‘Telling tales? Myth, memory, and Crickley Hill ‘, Memory, Myth and Long-Term Landscape Inhabitation, eds. Adrian M. Chadwick & Catriona D. Gibson.

[24] For earlier comparisons of such processes, see K. Jarrett (2010) Ethnic, Social, and Cultural Identity in Roman to Post-Roman Southwest Britain.